I am unusually drawn to Cottonwood. The smell of the sticky golden resin that can be found on its buds, petioles, and sometimes leaves is one of my favorites that exist in our world. This love is so great that I wear a perfume made with Cottonwood resin as a base. I rub the salves I make from this plant on my skin and face just to feel what I feel when I smell it. Like all plant-based scents, it ignites the bypassing of language and goes directly to that primal place of ancestral connection beyond just our human kin. Maybe I love it for that, for that immediate place it takes me, that kind of forget the small talk and the everyday menial sense of things and be in this feeling that our bodies are one part of a greater whole in time and space.

There is something deeply ancient and grounding about Cottonwood's scent.

Being in our world as a highly sensitive person, the air is filled with information and stimulus. We need plant based scents that bring us as sensitive humans but really all humans- back down to the old, back down to ourselves when our heads are filled with details, tasks, news, social nuances. It carries us to a safe place inside, usually. Personally, Cottonwood makes me feel comfortable in my skin again. Scents like Cottonwoods' invoke a feeling of laying at ease in wet soft moss inside my own body, under the very trees themselves that live in their own dark forest groves. Or, laying by a river, cool and quiet, with the soft breezes fluttering through, sending me wafts of the tree's scent, or noticing puffs of the tree's cotton-like seeds in Spring.

I didn't grow up with this tree around me. I barely even grew up with Willows (Salix spp.), a Cottonwood cousin, which has similar ecological preferences, medicine but a slightly different scent. Cottonwoods are in parts of the South (Populus deltoides), but it also appears in areas like the Great Plains, the Rockies, the Pacific Northwest (Populus trichocarpa, Populus balsamifera) and into Canada (Populus balsamifera, Populus tremuloides, Populus trichocarpa on the West coast) where various species of the tree grows in great abundance. In the Southwest, Cottonwoods (Populus deltoides var. wislizeni) follow the waterways or grows on the land above water. Or the Aspens (Populus tremuloides) find themselves established at higher elevations scattered across the continent.

An excerpt from a post, "Plant Stories from the Sagebrush Salve": (written when first meeting Cottonwoods across Turtle Island)

Black Cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) from near Sierraville, CA. 2016.

"I thought my first experience of Cottonwood was on the west coast. But, now that I have been thinking on it all winter, really reflecting on my first experiences with certain plants, I now remember vividly first encountering it while camping for a few weeks in the Finger Lakes region of New York in 2011. [...] I had some time while I was there to look at the plants as well as visit my friend Mario who was studying with 7song at the time. In a wooded grove on the land, there was a big towering tree in an opening by a creek. It was one of those picturesque kind of forest grove openings, where the area around the tree was clear as if I could set my sleeping bag down right there on the soft ground and stare up at the giant limbs without any obtrusion from mid story trees. I thought the tree was a White Birch at first, as the upper limbs were white and gray and Birch species did grow around the area. But, as my eyes wandered down the massive trunk, I realized the bark was ropey and twisted, turning a muted gray at the bottom. I was astounded by it's size. I asked the landowner [...] and he told me it was a Cottonwood! That same summer was the first time I attended the Traditions in Western Herbalism Conference when it was at Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, and here too I started to see the Cottonwoods or cousins thereof.

I know we had Populus species in North Carolina, where I lived for years. Populus [is] the genus of Cottonwood species and Quaking Aspen. [We also] keyed Populus out on an herb school field trip at Thom and Renata's wild land in southern Kentucky. I read about the local southern Appalachian use of the sticky buds. I found a self published book written by an old resident of Sugar Creek Rd on the way of life in his holler when he was growing up. It was called "Sugar in the Gourd" by Ben Garrison. I lived in that same Appalachian holler for four years and still migrate back there, just outside of Asheville, North Carolina. The author wrote about the task they had as kids to collect the buds early spring for selling just like their Ginseng and Black Cohosh harvests. I never sought the buds out back then. In Ohio, when I worked with the United Plant Savers, Paul Strauss had also talked about "Balm of Gilead" which he used in his Golden Salve and I think his cough syrup. At the time, I didn't quite understand which plant this really was. He also used the propolis from his beehives in his medicine, and I was confused because they smelled and felt like the same medicine.

I encountered Cottonwood again while traveling in the Pacific Northwest where they grow in abundance. I was visiting friends and stopped to see Ted, who at the time was apprenticing at the Wilderness Awareness School near Seattle. I was at the school's campus with him for a weekend teacher training, and he told me I should take walks in the forest and harvest Cottonwood buds because they were perfect for harvesting at that time. The trees towered above Salal and Huckleberry, intermixed with thick groves of Western Red Cedar and other conifers. I had never quite experienced such thick wet woods. It was cold and damp in February, yet we were all warm covered in our woolens. [...]

During one winter, I found groves of squat small Black Cottonwoods. This was while wandering around on the Sierra Hot Springs property and the national forest beyond. Their crowns were broken off a million times sending up shoots from the base of their trunks. They grew along a dried out creek bed, one that seemed to stay dry for a few years during the recent drought in California. But this year, it is running strong. The grove was a journey to get to with the mud and snow mounds and even on my cross country skis it was difficult not to sink into the ground spots. The buds were small but easy to reach. I didn't realize they were Cottonwoods when first discovering the grove in the leafless time of the winter. Something told me to sit down, as it usually goes. After awhile of watching, I was thinking they maybe were Willows, as they also grow on the same wet corridor. Examining closer, I smushed and smelled some buds. I noticed the dead leaves on the ground all around were round and heart shaped. They were not long and narrow like most Willow. These were indeed Cottonwoods. And the leaf scars! So pronounced. Next to the lodge at the Sierra Hot Springs is the Fremont Cottonwood, big and towering with giant fat buds out of reach. Traveling [nearby] on crazy dirt roads skirted by Manzanita, Redroot, Sagebrush, Black Cottonwood, and Juniper, you reach higher elevations and meet the clonal Quaking Aspens, another Populus [species.}

I noticed them dominating the valleys hugging the waterways traveling through the heart of hot springs country in central Idaho, one of the most beautiful places I have ever spent time.

I've noticed them traveling up the Missouri River, following [the river] from St. Louis to Standing Rock. I've noticed them in the Tetons up high and low and Yellowstone. One version grew in the Great Basin on the way up to meet the Bristlecone Pines, fluttering their gold coin-like leaves in fall.

The species I use the most is the Black Cottonwood. Just because it is what I have encountered the most at the time of year they are ready to harvest (late winter and early spring before leafing out). The earthy resinous smell is one of my favorites. I don't mind the orange sticky fingers that come with harvesting them one by one, only taking a small portion from each tree. "

Since this post, I have traveled to Colorado and through Utah, into Montana and Idaho more, Oregon and Washington. I have a visceral memory of one summer after the Good Medicine Confluence: sitting in a hot springs near Durango, CO and watching the cotton-like seed puffs blow in the wind coming off of the trees that grew there and landing in the hot springs water.”

Left to right: Eastern/Plains Cottonwood (Populus deltoides) (looks so similar to Fremont sometimes but because of location it was found, I’m saying Plains), Quaking Aspen (Populus tremuloides) from the Tetons in Wyoming, and Black Cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) or a Black / Narrowleaf Cottonwood (Populus angustifolia) hybrid from the Great Basin National Park, Nevada. Collection and study from a 2016 road trip.

Populus genus - an introduction

Cottonwood seed fluff

The Marmot from USA, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

There are many species of what collectively are called Cottonwood. Officially, certain species are grouped together as 'Cottonwoods' and some are called Poplar, but as common names go, this can sometimes get confusing, as there are trees called Poplar that aren't even related (ie. Tulip Poplar or Tulip Tree, Liriodendron tulipifera, on the east coast).

Another group of trees in the Populus genus that aren't usually called 'Cottonwoods' are the Aspens.

The 'Cottonwood Group' within the genus consists of closely related Cottonwood species. These include the Fremont (Populus fremontii) and the Eastern Cottonwood (Poplus deltoides), Narrowleaf Cottonwood (Populus angustifolia) as well as the Black Poplars (Populus nigra) which are found across Europe and have been heavily cultivated and bred.

There's also the Plains Cottonwood (Populus sargentii) found in the Great Plains states and into Canada. It is disputed as to whether it is subspecies of the Eastern Cottonwood. As of Fall 2022, the consensus is that is in fact an Eastern Cottonwood.

Many of these Cottonwood species hybridize, especially Narrowleaf Cottonwood and Black, which in the past has been considered a separate species. Sometimes it is hard to fully tell the different species apart, especially too because they can morphologically vary.

Riparian area in Cedar City, Utah with Narrow Leaf Cottonwoods growing with Russian Olive, Salt Cedar, Willow and Rose, Three-Leaf Sumac and Wild Crab Apples.

Trees in the Populus genus are male and female. Their catkins ('atcho, according to the Navajo) are dioecious, meaning male and female flowers occur on different trees. The male catkins produce pollen and the female seeds are shrouded in magical cotton-puff like hairs that float in the air, cover the ground, waterways and walkways in the Spring and into the Summer.

The leaves have flattened petioles, which is the leaf stem basically, and when the wind flows through the trees, they shake and ‘quake’ in a certain way that is unique and distinct. ‘Quaking Aspen’ in the Populus genus is even named after this way the leaves react to the wind.

The trees of this genus have prominent leaf scars that form a triangle-like shape. You can ID Populus easily in the winter from these tangible leaf scars in addition to their aromatic, swollen, burnt colored, & layered multi-scaled buds. The species can sometimes be narrowed down by noting the leaf litter on the ground if it isn’t the growing season. The bark can be gray, white or a tint of brown and vary in texture depending on the species and age of the plant. The bark varies according to age as well, and younger trees have smooth bark, and the older trees often have thickly braided and deeply furrowed bark.

Cottonwoods need plenty of water and sun, and without those things, they don't thrive. When they have those things together, they are a keynote species of their ecological zone providing shade for plants and animals that need it. They provide rich leaf mulch for the land surrounding them, important nutrients for other plants to survive. They also shade and keep waters cool, especially important in hot summers. They provide habitat for birds and other critters that take refuge in their stands. Habitat is also created by their branched and limbs breaking, as Cottonwood has really soft wood. This breaking is the bane of an urban arborist’s existence but is vital to the health of riparian areas where Cottonwood thrives.

Cottonwoods grow mainly from seed germination in typical flood events in the riparian areas where they prefer to grow but sometimes do reproduce clonally, and Aspens tend to prefer to reproduce clonally. Aspens in deep history reproduced more often from seed especially when fire was a more regular occurrence.

Despite the fact that introduced plants like Russian Olive and Salt Cedar are villainized for replacing Cottonwood and Willow habitat, Cottonwoods are also hated for being ‘messy’ and having soft wood. In fact, people talk about Cottonwoods as if they are useless and evil trees. Cottonwoods and Willows, Mule Fat and other associated riparian species that grow with Cottonwood, thrive when there are regular flood events. Dams, overuse of water for agriculture, and ag runoff among other things have affected the ability for Cottonwoods to thrive and for new trees to germinate, and more drought resistant and polluted water resistant species like Salt Cedar and Russian Olive have come to dominate the riparian spaces where once they did not exist. These plants are also providing food and creating habitat. These introduced plants have been villainized but they also are responding to the conditions we have created by mis-using water and land. Ecologists Kollibri terre Sonnenblume and Nikki Hill write about this in their research zine ‘The Troubles of Invasive Plants.’

Riparian area in Cedar City, Utah with Narrow Leaf Cottonwoods growing with Russian Olive, Salt Cedar, Willow and Rose, Three-Leaf Sumac and Wild Crab Apples.

Since Cottonwoods are sometimes the only trees around and often were the best shade during hot summer days, they have historically been places of meeting.

Cottonwood trees are some of the biggest broadleaf trees in the West. In the east, there is a lot of competition for this since there is more broadleaf tree diversity.

The Big Morongo Preserve near Joshua Tree, CA, features a riparian zone. Plant lists for the preserve include Cottonwood forests paired with Alder, Yerba Mansa, Mesquite, Desert Willow, Willow (the Salix) and more can be found on their website here. Cottonwoods can be found in varying riparian zones across the west and their paired plant kin change depending on the place. In Colorado you may find them growing with Three-Leaf Sumac, Crab Apple, River Birch, for example.

I attended a workshop with herbalist Dara Saville one year at the Good Medicine Confluence in Durango, Colorado on the future of plants in the Southwest due to global warming. She discussed the changes that could happen in the desert with over-consumption of water especially in new track home developments that aren't designed with water sustainability in mind. Her Yerba Mansa Project on restoring and educating about the Rio Grande Bosque ecology which includes Cottonwood in its mix is located in Albuquerque, NM and can be found here.

I interviewed Dara Saville on the Ground Shots Podcast about this project, you can listen here.

Historically, Cottonwood bark has been used by native folks for making pouches and baskets, for carrying food and other goods. It was used to make looms, prayer sticks, for friction fire making, tinder and for games by the Navajo.

Cottonwood also is used for firewood, even though it is soft and doesn’t have high BTU’s like harder woods do. I wouldn’t build things out of it, though for spoon carving and friction fire kits, it is great.

Salicaceae family

The Salicaceae or Willow plant family comprises mainly of the Cottonwoods, Willows and other members.

Salix sp. near North San Juan, CA. 2015.

Willow, Salix spp. (K'ai', or K'ai'lipAh - Navajo) is the most recognizable member of the Salicaceae family besides Cottonwood which is the focus here. Willow is in the Salix genus and encompasses a number of beautiful and variable species. All members are dioecious and have catkin flower structures, as I mention throughout this article, which designates male and female flowers on different plants. I still am not very good at keying out different Willow species. Some are very different looking and some look pretty similar. And of course, some hybridize. It just takes some time, focus and attention to cue in on them.

Salix sp. near North San Juan, CA. 2015.

Most members including Cottonwood/Aspens (Populus spp.) and Willow (Salix spp.) contain salicin and methyl salicylates. Salicin is a key pain-relieving component of both Cottonwood and Willow, so its no surprise that that common aspirin that we know today is derived from that compound. When my wisdom teeth were coming in and I had achey jaw pain that would keep me up at night, I took capsules of Willow which were extremely helpful for managing the pain. Methyl salicylates are also found in Birch, Meadowsweet, Wintergreen and other plants. It is the compound that gives them their winter-green like scent, flavor and is also extremely anti-inflammatory.

Willow contain tannins and I have been told they would make a good bark tanned leather. I have not tried it! I would like to. I’ve seen other people’s bark tan experiments with Willow though turn out pretty well.

Salix sp. near North San Juan, CA. 2015.

Willows also love the water and riparian zones, providing habitat for wildlife and soil stabilization.

In 2020 during the Colorado Trail Plant-a-go walk with ethnobotanist Gabe Crawford, we observed how much Beavers and Willow depended on one another. I have seen this relationship elsewhere too, but in Colorado it was really neat to see on foot. Alpine species of Willow tended to be sometimes the only shrub above the tree line able to handle the harsh environment. As soon as the snow melts or the springs leave the earth at high elevation, you start to see beaver activity. Beavers love to eat willow, and when they are building their dams, they often stash willow around their building and inevitable plant them in the dams, where they send down roots. Because Willows have a rooting hormone in them, used often for compost tea in seed starting, they root easily. These dam systems keep water on the land, create habitat for animals and other plants and also keep the water table high by allowing ground water to be brought upwards. Beavers and Willows are essential for ecosystem health.

Willow basket by Aganaq Kostenborder.

Basketweaving traditions exist practically anywhere Willow grew, including in Europe. Some folks strip the outer skin off of the Willow to weave baskets that look almost white. You can also harvest Willow bark from tree formed Willows and weave them plait-style into baskets.

Populus trichocarpa

Black Cottonwood

nekw’nikw’az, according to the St’át’imc & Splitrock environmental, a native owned herb company out of Canada

or T'iis (Navajo)

Elbert L. Little, Jr., of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, and others, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Black Cottonwood buds and male catkins

By Thereidshome - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6315224

Black Cottonwood is predominantly found in the Pacific Northwest and California, and scattered across the West in general. It’s range extends from Alaska all the way down to Mexico, an unusually wide range given how different the conditions are in these areas.

Black Cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) from near Sierraville, CA. 2016.

Black Cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) has an elongated leaf and gently crenate margins. It’s leaves aren’t as heart shaped as Balsam Poplar, Eastern COttonwood or Fremont Cottonwood, but not narrow like Narrowleaf Cottonwood. Sometimes the leaves are sticky and glossy, glowing in the sun. The leaves can be large and wide, and on other occasions they are small and narrow. The top surface of the leaves tend to be a darker green, and the underside a lighter green. It has long, narrow and small sticky buds. It has gray smooth bark when younger and furrowing with age. It is generally dioecious like other Cottonwoods and Willows, with male and female catkins occurring on different trees.

It is not the same as the Black Poplar (Populus nigra) in Europe, which is the source of many cultivars in the states, including the short lived and easily toppled Lombardy Poplar that my dad has planted throughout his life as a mainstream horticulturist.

Black Cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) from near Sierraville, CA. 2016.

It has a diverse number of phenotype expressions. It easily hybridizes with Narrowleaf Cottonwood (Populus angustifolia) which grows predominantly in the southwest and parts of the Rockies. According to Stuart and Sawyer's 'Trees and Shrubs of California,' it also hybridizes with Fremont Cottonwood (Populus fremontii).

This is my favorite Cottonwood for medicine like I mentioned in the Sagebrush Salve stories above. I have traveled up along the Yuba River in the California Sierra foothills and found it in the waterways exponentially, the higher I go. I have seen them in instances looking really gnarled and practically dead from flooding damage but having fresh new sprouts from the still living parts of the tree come alive. Also in these instances, I tend to see new sprouts come up along the ground in the seasonal stream beds or flood zones.

Some folks feel like Black Cottonwood is in major decline due to development in certain areas which affect the water table. This species of Cottonwood has particularly resinous buds, compared to other species. I gather from them all, but this one is my favorite to use. Their buds are often not as big as Balsam Poplar or Fremont, though.

Populus fremontii

Fremont Cottonwood

T'iis (Navajo)

Fremont COttonwood tree near Moab, Utah

Fremont COttonwood near Moab, Utah

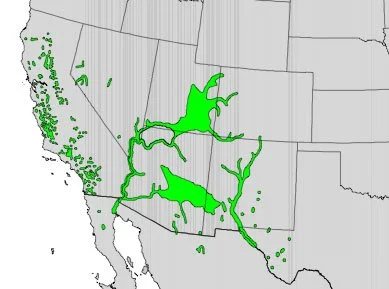

Fremont Cottonwood is found in the west and parts of the Southwest and across California.

Fremont Cottonwood Range

U.S. Geological Survey., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fremont Cottonwood was named after the controversial U.S. military general and independently funded western 'explorer' John C. Frémont, who pushed as many 'discovered' things as he could to be named after himself. I wish there was a way we could rename things like this rather than keep the designations of common and latin names that are most always named after white male botanists, mappers or 'explorers.' Though I am interested in botany as a universal language for speaking about the ways that plants are genetically and morphologically similar, and how their similarities change according to place and habitat, I am also interested in a kind of 'undoing' of the colonial aspects of these namings and categories. I am constantly acknowledging how botany has its place for correct identification of plants in an age of 'unnoticing,' as a way to prompt folks to pay more attention and see the relationships between things. It is useful for talking about plants with folks who don't speak the same language, or looking at books in other languages. It has been incredibly useful for me to navigate a nomadic life: I can orient myself in a place by looking at plants and knowing what things are or are related to simply by their leaf structure or number of petals. I am impressed by how these categorizations and relationships work. But, I am equally at awe with how plants bypass our wants for 'gridding' and imposing order on a seemingly wild and chaotic map of 'nature' by not fitting easily in our classifications (hint: hybrids). FYI, A good book that discusses the politics of Fremont, mapping and our need to 'grid' can be found in a favorite book of mine, 'The Void, The Grid and The Sign,' cited at the bottom of the article.

Fremont COttonwood near Moab, Utah

Fremont Cottonwood has wide heart shaped simple leaves with roughly scalloped or crenate leaf margins. Like Black Cottonwood, its leaves are often covered in splashes of resin and are a vibrant yellow-green color. It has exaggerated leaf scars and large pointy resinous buds. This species of Cottonwood can get huge! It often is a beautiful towering tree with long hanging limbs and branches that swoop out and down towards the ground. Often the grow straight up in forest, and like I’ve mentioned before, dominate flood plains. In some regions, the hillsides are covered in smaller trees and shrubs like Pinon or Juniper but as soon as you reach the water, giant Cottonwoods grow.

It grows in the Southwest, southern and central Rockies, and scattered across California. When looking at maps of its range, it is fascinating to see its snake-like lines which follow the rivers and riparian areas. Like other Cottonwoods, Fremont Cottonwood groves indicate the presence of groundwater. In some places in the Southwest, Cottonwood is one the only trees around that provide substantial shade. It also is a reliable source of decent firewood in the winter.

The Rio Grande or Alamo Cottonwood (Populus wislizeni) of the southwest was originally considered a subspecies of Fremont Cottonwood, but it has bee decided that it is more genetically similar to the Eastern Cottonwood.

Riparian area near Moab, Utah with Cottonwoods, Willows, Salt Cedar, Russian Olive, Three-Leaf Sumac and more.

Fremont Cottonwood leaf up close

Joe Decruyenaere, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Populus tremuloides

Quaking Aspen / The most ancient Tree

T'iispaih / T'iispèlh (Navajo)

Halava, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Quaking Aspens are some of the oldest trees on earth, forming dense cloned stands sometimes acres in size. Their leaves have a gold-coin like shape and flutter magically in the wind, seemingly in cadence. Some stands in the Great Basin, where some of these photos below are shot, are up to 8,000 years old, just under elevation from the Bristlecone Pines which are also some of the oldest trees on earth. There are other groves that are aged at over 80,000 years old, officially the oldest on earth. I recommend reading the incredibly fascinating Wikipedia article on Pando, the ancient grove in Utah and the troubles its faces here. These trees fool you because when you are walking through a forest of them, their trunks don't seem big or especially old, which is not an indicator of age. This is also the case for the Bristlecone Pine, which seems rough and tumble but not dramatically large or tall (See my blog post on the Bristlecones here). The individual trees can live to be about 100 years or so but when they die back, their roots still live, and another tree can sprout back in its place.

Quaking Aspen in The Tetons, Wyoming 2016.

Newcomers will confuse the tree with Birch, given its similar smoothish gray to white bark, and sometimes these trees do intermingle like in some New England States. But, Quaking Aspen, as noted, is in the Salicaceae or Willow family, where Birch is in the Betulaceae or Birch family, another group entirely.

Aspens can grow at higher elevation and while they aren’t necessarily a riparian species, they are associated with present ground water. They Cottonwood cousins prefer to hug closer to riparian zones when possible. They reproduce mostly from root sprouts and less so from seeds given that stands are usually male or female and the seeds are not viable for long. According to the various books I have looked through, the Aspen groves in New England reproduce from seeds easily, but the groves in the West have had a harder time reproducing that way and rely almost solely on vegetative reproduction. This is due to change in climate and fire suppression. It maybe has been thousands of years since Aspen groves in the west have reproduced successfully via seed. The groves are incredibly responsive to fire and disturbance, of which they are evolved to survive and thrive from, but because of fire suppression, some groves have suddenly died off or get taken over by conifers. They have seen more than pretty much any other organism on earth, if this isn't wisdom, I don't know what is.

We noticed on the Colorado Trail Plant-a-go walk in 2020 that Aspens grew abundantly in avalanche shoots, where snow would take out entire forests, top soil and rock and deposit the tumble down below. Aspens love disturbance, so Aspens and other disturbance loving plants came back with fierceness along those corridors.

Aspen bark in a grove at high elevation, Great Basin National Park, Nevada, 2016.

White Birch, not related to Aspen but often confused with Aspen.

Joe Decruyenaere, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Aspen grove at high elevation, Grand Tetons, Wyoming, 2016.

Aspen grove, Great Basin National Park, Nevada, 2016.

Aspens showing fall color among the conifers including Juniper, Pinon Pine and Limber Pine. Great Basin National Park, Nevada. 2016. One of my favorite places on earth!

Populus balsamifera

Balsam Poplar

Elbert L. Little, Jr., the United States Geological Survey, an agency of the United States Department of the Interior., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ryan Hodnett, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Balsam Poplar or Balsam Cottonwood is the Populus species of the great north. It grows in Canada and into the northern Great Plains and Midwest, dipping some into New England. It is likely the species that grows at Windblown Cross Country Skiing in southern New Hampshire, where I worked for several winters. I remember Andy, who has lived there his whole life, telling me that it popped up all over the place on the land and had 'invasive' tendencies in his eyes despite being a native species. Like I mentioned earlier, sometimes Cottonwoods can reproduce clonally. In the far north and the east, where there is more water, Cottonwoods don’t necessarily hug to the waterways like they do in the Southwest and west where rain comes in more distinct seasons.

Its leaves are heart shaped, but wider and more pronounced than Cottonwood. It doesn’t have scalloped or toothed margins that are obvious or dramatic like Fremont Cottonwood or Eastern Cottonwood.

Balsam Poplar from the north and the Eastern Cottonwood (Populus deltoides) will readily hybridize where they co-mingle and form the Populus × jackii, which is the official scientific name of the famed 'Balm of Gilead' that Paul Strauss so swears by in his medicine making. The 'x' signifies that it is a hybrid that cannot a breed a true version of itself.

But, It seems like Balm of Gilead is a name used to describe all Cottonwood resins commonly. The name is based off of an aromatic plant that is unrelated to Cottonwood.

Narrowleaf Cottonwood

Populus angustifolia

Narrowleaf Cottonwood, southwest Colorado, possibly a hybrid.

Narrowleaf Cottonwood grows mainly in the upper Southwest and scattered across concentrated areas in the Rockies. On the Colorado Trail Plant-a-go walk in 2020 across Colorado, Gabe Crawford and I saw it growing at lower elevations by rivers. It grows with Fremont Cottonwood at lower elevations in the Southern Rockies and deeper Southwest. It also seems to be able to grow at a wide range of elevations in general.

Elbert L. Little, Jr. // U.S. Geological Survey, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s leaves are distinctly narrower and lanceolate compared to other Cottonwood species and also could be mistaken for Willow, its family relative, by the untrained eye.

It’s leaf morphology varies, and like I’ve mentioned, this species easily hybridizes with Black Cottonwood as well as most of the other Cottonwood species, hence why it might be hard to always get a confident ID. Narrowleaf Cottonwood like other Cottonwoods, is often planted as an ornamental and thrives and spreads when planted out. It’s range is pretty vast, like other Cottonwood species, and stretches from Canada to Mexico in scattered pockets of abundance. It is especially common in Colorado, Utah and dipping into northern New Mexico. You’ll see it hugging riversides and riparian zones mingling with Willow, wild Rose, Hawthorn, Milkweeds, among other plants.

Eastern/ Plains Cottonwood

Populus deltoides

By Robert H. Mohlenbrock @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA NRCS. 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office guide to plant species. Northeast National Technical Center, Chester. - http://plants.usda.gov/java/largeImage?imageID=pode3_004_ahp.tif, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7733389

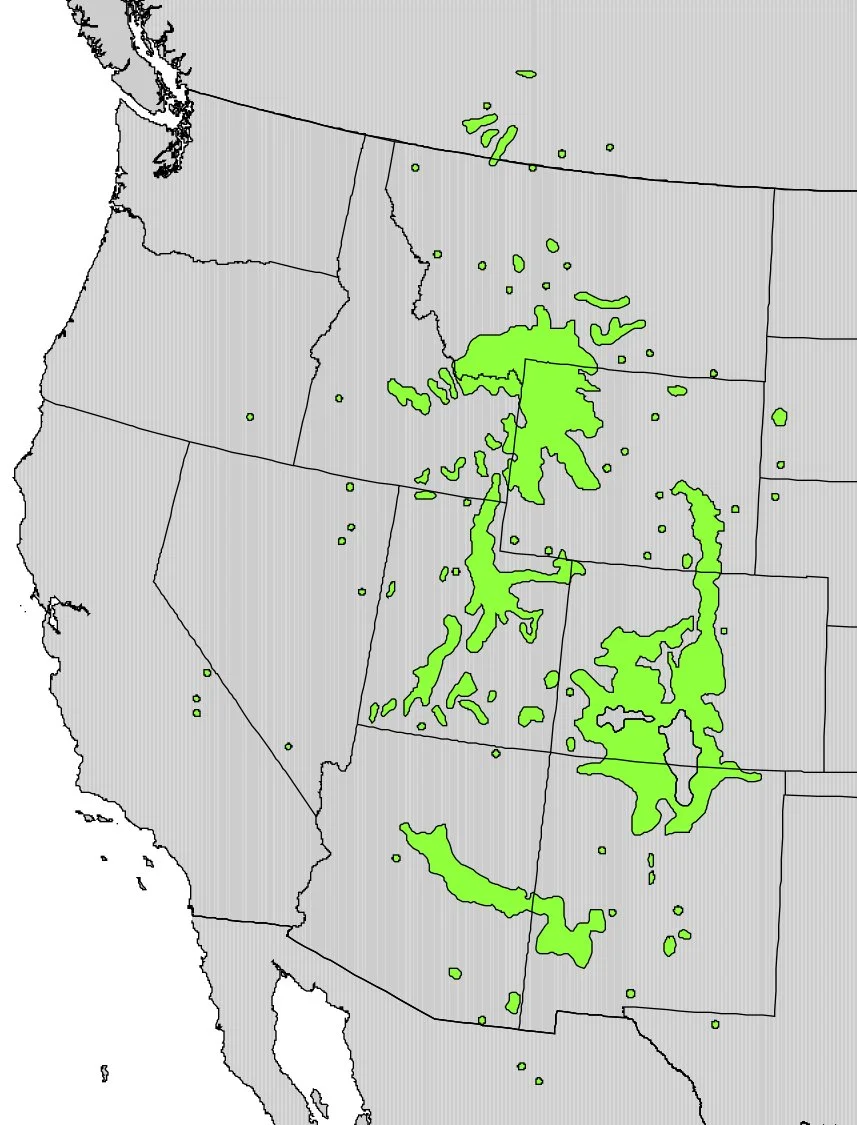

Eastern Cottonwood has a wide range and has several subspecies that at times have been considered separate species. Genetic testing has given us enough information to understand that these ‘different’ trees have a genetically similar lineage. Because of this, it has such a large and diverse range of where it grows.

Its leaves look similar to Fremont Cottonwood, with toothed margins. Like Aspens and other Cottonwoods, the leaves shake in the wind and produce a certain magical cadence, making it easy to notice them. Most Cottonwoods including this species produce yellow leaves in the fall, and in drier years lose the leaves earlier. Like other species of Cottonwood, this one loves water and can be found along big rivers like the Mississippi. It needs flooding to germinate its seeds and can thrive also in moderately wet disturbed soils. This species doesn’t reproduce clonally, but other species of Populus do.

Like other Cottonwoods have the potential to do, this tree can grow really large and really fast. It has soft wood like the other Cottonwoods and can also live to be decently old at several hundred years.

By Elbert L. Little, Jr., of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, and others - USGS Geosciences and Environmental Change Science Center: Digital Representations of Tree Species Range Maps from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. (and other publications), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29777015

Populus deltoides subsp. deltoides, ‘Eastern’ -mostly found to the east

Populus deltoides subsp. monilifera - ‘Plains’ found in the plains up into Canada

Populus deltoides subsp. wislizeni - ‘Rio Grande’ found in the Southwest, considered a subspecies of Fremont Cottonwood to some scientists

By USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Herman, D.E., et al. 1996. North Dakota tree handbook. USDA NRCS ND State Soil Conservation Committee; NDSU Extension and Western Area Power Administration, Bismarck. - http://plants.usda.gov/java/largeImage?imageID=pode3_010_avp.tif, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7733080

Medicine of / Harvesting Cottonwood

The buds, leaves and inner bark of Cottonwood are its medicinal components. The buds are usually best to collect in late winter before the leaves come out. Be aware that your hands will get sticky and whatever you put the buds in will get sticky too. Even if it is a cold day and the buds aren't super tacky, they will become so when you bring them into your warm house. I have also seen storms knock big branches down and beavers fell Cottonwood trees, making the buds easy to harvest. Another Beaver and Willow family relationship win! Sometimes they are high up and unreachable. On other occasions, the trees were small enough to reach the buds, living on dry creek beds or riversides. If you miss them at low elevation, and you're in the mountains, move up higher, they've probably not leafed out yet. Sometimes the buds will be so thick with resin that they will literally 'slow drip' an amber-orange color down the bud or have a kind of frozen red orange resin drip coming off the bud. If you squeeze them, especially when it is warm out, you will get your fingers covered in sticky resin, and increase its already potent aroma wafting in the air.

Given their high resin content, infusing them in strong alcohol or oil is best. I honestly have harvested them in late fall and they have seemed just as potent as late winter. It was a matter of opportunity since the limbs had fallen and I noticed the buds were full of resin, even in December. I would only collect a handful of buds per plant and try to avoid the terminal buds at the end of the tree's limbs as a best practice harvesting.

Aging the oil will increase the complexity and flavor of its scent, if you can wait! Different species have different subtleties of scent and flavor. Even the richness of the color can vary depending on the species and location.

Black Cottonwood just leafing out on the North Fork of the Yuba River, 2015. These leaves are sticky!

WInter 2015 harvest.

The leaves can be harvested in the summer and made into a tea. The inner bark of Cottonwoods and Aspens can be harvested for medicine in fall or spring. It’s mostly used as medicine but can be used as food if needed too. To harvest the bark from an Aspen, I would recommend only harvest a limb or two from each tree, though Aspen groves tend to be massive and one big uni-organism clone, rarely phased from disturbance. In fact, they love it. In actuality, it maybe increases their growth because it doesn't actually kill the plant who's roots persist underground. Cut the outer bark off of the woody core with a sharp knife on a tarp into strips. I leave the outer bark of Aspen, others say to remove it. If you're harvesting a Cottonwood's bark, this will be a harder job and removing the outer bark is recommended. I would recommend gathering inner bark from a younger cottonwood tree or also use a branch or limb to gather. Dry the bark pieces in a paper bag with plenty of room and moving frequently or lay out as strips if you’re not in a humid place. In the South, dehydrators might be best for drying inner bark, if you live there, you know- everything can mold! Try to avoid drying in the direct sun. Cut up the bark into smaller pieces if you can for easy tea, oil or tincture.

Cottonwood buds infusing in oil

I mentioned before when talking about Willow and Cottonwood medicine, that the plants contains anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving compounds. Aspirin is derived originally from these compounds. It is also diaphoretic internally (makes you sweat) and diuretic (makes you pee).

An infused oil or salve made from the buds (and sometimes bark) rubbed topically onto sore joints, sprained areas, swollen or bruised injuries or achey muscles can provide mild relief. The medicine topically is also amazing for irritated skin and burns, sunburns, and even mild fungal issues. It can promote skin regeneration and is a great addition to any kind of skin-healing salve.

To infuse the buds in oil, first pick them off the branches and then put into a glass jar. I would not fill the jar up all the way with the buds. If it was moist out, I would let them dry out a little before infusing, as they can ferment or mold. Fill the jar of buds up with a basic oil like Olive Oil and when the infused oil is done, which could be a month or a year, strain through cheesecloth before then making a salve with beeswax.

The bark of Cottonwood can be included internally in a tea for UTIs as pain relief and because it is a diuretic which is helpful for UTIs. The bark of Cottonwood and Aspen can be used in digestive formulas internally and could make a creative addition to bitters formulas in combination with other herbs.

A tea of the leaves or bark internally is also helpful for mild headaches, diarrhea and even fevers.

The buds and bark are helpful included in immune formulas as tea or tincture for its anti-microbial effects. The infused oil can last a long time, even two years after one harvest. It would be a good addition to an oil or salve formula as a preservative.

Michael Moore cites a curious sounding pain relief bitters recipe in his Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West that includes Aspen bark, Licorice root, cloves and brandy.

The Cottonwood buds or bark tinctured in alcohol is helpful as a stimulating expectorant for stuck thick mucous and I have seen it used in throat and cough formulas by various herbalists across the country.

I cited in the beginning of this piece, the 'feeling' I get from Cottonwood's scent that is 'beyond language.' This plant is incredible for moving emotional funk and nurturing self through depression, especially seasonal depression. Sometimes when my heart feels heavy, I put on a perfume made from the resin of this plant, and it uplifts my spirit.

As for the wildcrafting ethics harvesting parts of these trees, I would consider location and the impact of your disturbance. Given that disturbance often increases the populations or resilience of certain plants including Cottonwoods and Aspens, consider what kind of disturbance could be beneficial in engaging these plants when gathering medicine. In a riparian area suffering because of inhibited flooding and water flow, where the trees look like they are dying, I would refrain from harvesting their buds unless the branches fell to the ground. Favoring gathering from fallen limbs whenever possibly is probably a good idea overall. In the bigger picture, Aspens are in decline, but gathering a tree for bark medicine or a limb generally won’t hurt the stand, especially since they usually thrive in disturbance and is is part of why they are in decline. Don't take all the buds from a single tree.

Balm of Gilead is a common name used for the medicine of Cottonwood bud oil, or as a name for the tree itself. ‘Balsam’ and ‘Balm of Gilead’ have biblical origins and meanings referring to ointments, perfumes and ‘balms’ made from plants not related to Cottonwood that are no longer abundant. Groves of these plants were cultivated and planted in parts of the middle east. It seems wars were fought over these plants or in the midst of these shrubs which made a potent medicine and had a strong scent. The name Balm of Gilead was likely given to Cottonwoods, the buds or the infused oil because of the strong scent of the resins and the association with the balm or salve that can be made with the infused oil. It seems that the word ‘Balsam’ can also just mean aromatic medicinal herb in some languages and histories. ‘Arrowleaf Balsam Root’ (Balsamorhiza sagittata) is an unrelated plant in the Aster family that has aromatic resinous roots used to make internal cough formulas among other things and likely got its common name as well because of its aromatic resins.

Propolis often smells like Cottonwood bud oil because bees use the resins from this tree when available and other trees with resins to make the propolis which protects the hive. Propolis is also medicinal tinctured and can be used in salves as well.

Formula for salves: Cottonwood buds, Creosote bush, Pine Sap

Formula for internal use in a cough formula tincture: Cottonwood buds, Redroot, Fir or Pine, Yarrow, Elecampane

Works Cited

Bowers, Janice Emily. Shrubs and Trees of the Southwest Deserts. Western National Parks Association. Tuscon: 1993.

Completely Arbortrary Podcast. Wrongfully Scorned, Rightfully Wronged (Black Cottonwood). Alex Crowson and Casey Clapp, hosts. June 23, 2022. Accessed October 2022.

Sonnenblume, Kollibri terre and Nikki Hill. ‘The Troubles of Invasive Plants’ Macska Moksha Press. Cliff, New Mexico: 2019.

Stuart, John D. and Sawyer, John O. Trees and Shrubs of California. The University of California Press. Berkeley: 2001.

Moore, Michael. Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West. Museum of New Mexico Press. Santa Fe: 2003.

Elpel, Thomas J. Botany in a Day. The Patterns Method of Plant Identification. HOPS press. Pony, Montana: 2013. 6th Edition.

Fox, William L. The Void, The Grid and the Sign: Traversing the Great Basin. University of Nevada Press. Reno: 2000.

Website. The Yerba Mansa Project. Web. April 1, 2018.

Elmore, Francis H. Ethnobotany of the Navajo. University of New Mexico Press. Santa Fe: 1944.

***Navajo names and uses in this article came from Francis H. Elmore's 'Ethnobotany of the Navajo' publication from 1944 which you can read through here. This publication is a great resource but also has its own issues that anthropological research can tend to have. I don't claim to be an expert on the uses of Cottonwood, Aspen or Willow in the ways that the wide range of native groups that had access to these plants used them. I am learning and trying to understand the context of their importance in different places by different people and not wanting to diffuse their uses into 'what all native peoples did' because that erases their individual identities. But, I admit my naivety. I attempt to cite their native names here and there, but also feel conflicted about how I as a non-native should or should not use these plants' native names. I may update this piece and others as I learn the native names (just like these complex latin names) for them by the different groups of people who lived with and used them. ***